By JULIANA KNOT

HP Staff Writer

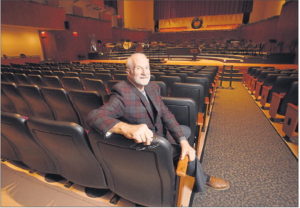

BERRIEN SPRINGS — Great music requires both spontaneity and conformance to the rules, according to Stephen Zork.

Zork, who is a professor of music at Andrews University, specializes in choral studies and leads the Chancel Choir at the First Congregational Church of St. Joseph. He has served in both positions for more than 30 years.

Last Friday, Zork led three choirs in the concert: “Welcome Christmas: Brightest and Best.” He said the concert touched more on the importance of justice and peace in the Christmas story, rather than the traditional Nativity scene songs.

Zork sat down with Herald- Palladium Staff Writer Juliana Knot to discuss how music helped him navigate his childhood stutter and how both spontaneity and rules are important in cultivating musicians.

What drew you to music?

I was involved in it from the age of 3. My parents had a pump organ that they took with them to a very remote part of Africa when they went out there in 1953, shortly after I was born. Within a year afterwards, I started playing at the pump organ and figured out literally how to make this (motioned at stomping his feet) and how to pump the pedals. My parents tell me at about the age of 14 months I was like pumping pedals and just making sounds.

But they knew I was interested in music, and they really supported (me). So by the time I was 3, I was actually having absolute fun with making music. I didn’t know whether I was gifted or not; my parents didn’t know whether I was gifted or not. It was just that I was the one that took a fancy to this mechanical organ. It was impossible to have pianos where they went because they wouldn’t stay in tune.

But somehow this little, miniature, tiny pump organ was the one that they brought with to this very remote part of Africa where I lived for my first 18 years actually. I didn’t leave Africa until I came to the States to start college. My parents were missionaries.

So I got interested then, at the age of 3, playing. And it was always for pleasure, always for pleasure, and I detested it when we got into any situation where someone wanted to take over and rehearse us and make it perfect or get it better or whatever.

That to me, took all of the fun out of it. The ironic part is that’s what I spend my life doing.

I was going to say. What led to the transition from just singing for pleasure to rehearsal and perfection?

Because I was a young kid, I grew to detest the manner in which we would rehearse for perfectionism, for excellence. I felt like when I started making music with friends later on in life – elementary school, high school – I was always told, “Zork, you tell us what to do. You always have impressions, and you always have an idea.”

I didn’t think twice about it, but after I got really kind of animated with my social group of musicians and kind of got demanding after a while, they said, “Hey Zork, chill! You’re taking the fun out of it.”

That happened when I was about 15 years old, and I didn’t realize it.

I was bound for that kind of work, but if I was going to do that kind of work, then I’d better learn some of the psychology of awakening music from people, inspiring them, helping them discover their potential, working them to a level of excellence but not to confuse perfectionism with excellence.

My negative experiences as a younger kid was … excellence was never the word. You got to be perfect. You got to be perfect. That took all of the fun out of it.

When I went into my last year of high school, my friends told me, “You should go into music.”

I had no idea, because for me, music was always just pleasure, just fun. That’s all! And I didn’t think that until my friends told me, “No, you should do it.” So, I did.

So, correct me if I’m wrong here, but it feels like choral performance is your hallmark, your focus.

Yeah, it definitely is; it definitely is. As a young kid, what I got the most pleasure from was singing, and at a very young age, I was taken to choir festivals where I could actually be a participant, really, the high points, high points of my life.

Just altruistically, I had at this point in time, as a young kid enjoying singing, I never had a desire to become a professional singer or even to become a conductor. It was just something that was so cathartic for me.

When I look at it years later, I knew that music was an important vent for me at an age where I had gone through some horrific childhood trauma that followed me up into the teens, even the late teens. It was singing that got me through that, but I only noticed that in hindsight.

So it was always cathartic, singing. There was four years of my life that I went through when I lost the ability to speak. I could make sound; I could sing, but I couldn’t speak because I would stutter horribly. So I taught myself how to start sentences pretending to be singing the sentence, the beginning of it.

Years later, I realized that was one of the unorthodox ways of teaching the king of England, who suffered from a very similar problem.

Right, “The King’s Speech.”

Yeah, and that his speech coach was totally unorthodox, but did all of the things. I’m looking at that movie for the first time in my life, when I saw it. I’ve only seen it once, and I sobbed, because this was me! My parents took me to psychiatrists, and I went through all kinds of treatments for anxiety and depression and all that kind of stuff.

It was the singing that got me through, but not even they realized it.

If you don’t mind my asking, when was stuttering an issue for you in your life?

It was from the ages of 8 though 16 – about eight years – and the last four years of that was the inability to engage or start a sentence. If I could … respond to something quickly without thinking about it, I could (speak).

So, it was a very lonely four years of high school, because I was very animated, I had lots to say and I expressed it more through music, than I did verbally.

Literally, music is and singing is what got me through that, so I didn’t have the ability to think, “Yes, I will amount to something as a professional teacher of voice and conducting” at that age, because I had zero self confidence.

When you can’t speak because you’re humiliated by stuttering or you just can’t start a sentence, because you just can’t start it, it’s just too much effort to start a sentence.

If you’ve been around people who have a hard time speaking, it’s a lot of work.

You mentioned that part of this career is awakening this desire for music and this confidence to perform and create music. What does that require? What do you need to instill in a student to make that happen?

You have to recognize the value, the transcendent power of musical expression. It is definitely a different kind of expression from a different side of the brain than speech and drama. There are many people who are trapped in their own narrative and don’t know other ways of expressing themselves, because they might feel inept as a verbalizer.

Some people find it through writing. They don’t speak well, they don’t socialize well, but boy, give them something to write, and they’ll write.

When it comes to expressing through music, it is something that literally is in a different part of the brain and that literally allows expression to take place from a different brain center. It allows people, it allows all kinds of people to find a common ground in an area that is also associated with vulnerability.

Musical expression is best experienced when you have mastered the art of submission and being vulnerable. Once you practice the rules – practice, practice, practice – you are eventually going to have to perform. You cannot remain in the practice mode; you have to cross over into a vulnerable mode.

And you have to get people to see the value in spontaneity, and you teach them the importance of release. Just be spontaneous, impulsive and (you will) discover capabilities, and that’s what I do when I meet with people for the first time in a group, like in a choir festival. I do stuff that is absolutely spontaneous.

We find out all of the things we can do with our voices. From that, we start the process of refinement. If you start with the rules first, you may never have people experience their potential or have the pleasure of spontaneity, the vulnerability.

Stephen Zork

Contact: jknot@TheHP.com, 932-0360, Twitter: @knotjuliana